A Year of Learning for Environmental Negotiations

Letter from the Editor of The State of Global Environmental Governance 2021

16 February 2022

Negotiating global agreements on climate action, biodiversity restoration, plastic pollution control, and other environmental crises is not easy at the best of times—and 2021 was far from that. Yet there were gains as the world navigated shifting waves of COVID-19 and unequal vaccine sharing.

Negotiating global agreements on climate action, biodiversity restoration, plastic pollution control, and other environmental crises is not easy at the best of times—and 2021 was far from that. Yet there were gains as the world navigated shifting waves of COVID-19 and unequal vaccine sharing.

Our report The State of Global Environmental Negotiations 2021 explores the highlights and lowlights of the past year. Dr. Jennifer Allan's opening letter puts this tumultuous year in context while looking ahead to the possible negotiating milestones in 2022.

I look forward to the year when these reports won’t start with a reference to the Coronavirus pandemic. This isn’t that year. 2021 started with optimism—early distribution of vaccines in the Global North—and ended with the spread of a new, highly transmissible variant and persistent vaccine inequity. The pandemic continued to take lives and livelihoods. It still shapes how we live and the ability of states to collectively address environmental crises.

On its face, 2021 seemed a lot like the year before—disrupted and difficult. But that glib assessment doesn’t give UN staff, negotiators, and civil society representatives their due. 2021 was a year of learning.

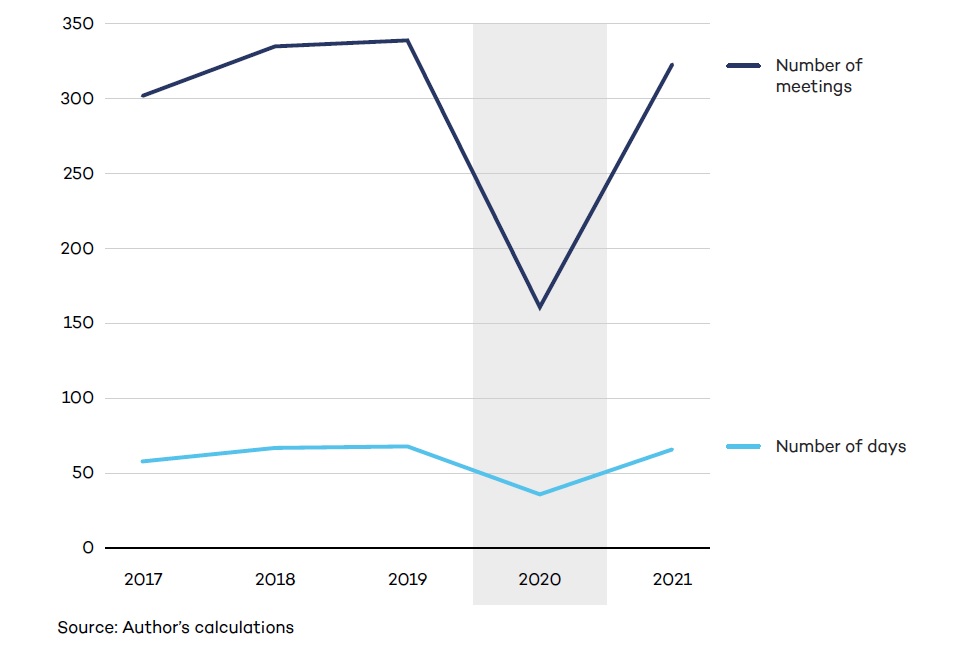

Online meeting practices evolved. We had “hybrid” meetings involving both online and in-person modes of work. Meetings spanned multiple weeks to allow for fewer hours spent online each day. They often rotated time zones, as delegates tried to juggle global governance and time zone equity with household labour, sleep, and their regular day jobs. Nearly everyone had a turn at a 4am contact group.

We saw the first in-person meetings since the pandemic began. The global community didn’t just tiptoe into normality with a small meeting. It leapt. The IUCN World Congress was thousands strong. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) saw over 40,000 people registered for the Glasgow COP. The venue only accommodated 10,000. Queues and complaints ensued. On the streets, up to 100,000 citizens marched for climate justice.

These forays into something nearing normal were test runs for the year to come. There were COVID cases at the Glasgow COP, but they had little impact on local case rates. More face-to-face meetings are very likely in 2022, with the new regimen of daily testing, masks, and physical distancing. Some dates are likely to shift, if (or when) pandemic conditions change. This is still a time of flux. Meeting dates and formats continue to change quickly.

We take stock of where various negotiation processes are given the continued disruptions in 2021, in Section 4. There were a fair number of meetings, but few that produced substantive outcomes. Many were informal gatherings, largely intended to keep environmental issues on political agendas. Countries inched forward on key issues, where they could. Important procedural decisions helped keep work programmes moving forward. The IPCC adopted a landmark report, as part of the Sixth Assessment Report, again warning us of the depth and urgency of the climate crisis.

Environmental destruction does not relent, even in the face of a world-altering pandemic. While governance stalled, the impacts of the climate, nature, and pollution crises were ever clearer. Postcards from a World on Fire documents 193 climate-fueled disasters across the globe. My hometown in northern Canada found itself under a “heat dome.” Temperatures reached 41°C; we’re far more accustomed to -41°C. More than 600 people died across the province, and 650,000 farm animals died near my hometown. Similar stories played out around the world, as floods and fires, droughts and storms caused upheaval. Many communities don’t have the advantages of a strong public safety net to support them during such times of loss. The pandemic will be over, one day, but the environmental crises are just heating up.

We rightly look to global institutions to address global problems. As ENB turns 30, we stand firm in our belief that multilateralism is the way forward. Global problems are increasingly intertwined. We document the growing inequalities amplified by the pandemic and how they threaten environmental outcomes in Section 3. Over 2020, these connections strengthened. In 2021, the UN Human Rights Council recognized the universal right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, with legal consequences that could affect environmental negotiations in years to come.

There is a clear trend in how global institutions are governing global environmental problems—pledging (see Section 2). It’s been around for some time, notably enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. In 2021, pledging seemed even more dominant. Perhaps it was a useful default, given that countries couldn’t get together to negotiate and adopt global rules. But to me, at least, it felt more fundamental. Most major meetings during the year revolved around pledges.

Pledges are promises. There can be guidelines to make them more consistent and even rules about reporting back. But ultimately, they are promises about what will happen in the future. The gap between promises and action is inescapable. While countries made climate promises in Glasgow, and countries and companies pledged “energy compacts” in New York, they also increased investment in fossil fuel production.

Perhaps, this gap is fueling the rise in climate litigation: 2021 saw many significant decisions. In the Netherlands, the Hague District Court ordered Shell to reduce its emissions by 45% by 2030 across all activities and scopes, marking the first time a company has been ordered to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions in line with IPCC reports and Paris Agreement goals. National and international courts have been expanding states’ duties of care regarding climate change, setting important precedents for future litigation. With litigation on nature and biodiversity also on the rise, we may see further landmark decisions in the year ahead.

We try to imagine 2022 to conclude the report. This year, it seems we are on more solid ground than last year... but to be fair, we have yet to be right in our predictions. The bar is comfortably low. 2022 could be a bumper year for environmental governance: new frameworks to govern nature and chemicals management; more climate ambition; new negotiations launched to address marine plastics and to establish a science-policy body for chemicals. And just in time, as the UN Environment Programme turns 50 and we mark 50 years since the landmark UN Conference on the Human Environment, which put environmental issues on the global agenda.

Ideally, we will end 2022 as happy as one little girl at the Cincinnati Zoo, who finally got to meet her world-famous namesake: Fiona the Hippo.